“I like the little head you sent verry much”: Encountering the encounters in the archive of the Natural History Society of Northumbria

By Peter Mitchell

Archives, if you spend long enough in them, have a fantastic effect of bending history around their own gravity. I did research for years in the archive of the East India Company and the India Office, and I learned very little about South Asia but an awful lot about administrative deskwork: I began to conceive of the British empire as an immense network of rooms, candlelit or shaded from a punishing sun, in which men sweated or shivered over the scratching of their pens while violence happened invisibly somewhere nearby. Working on an oral history archive about the NHS, I got to realise that if you want to understand a British person’s most intimate relationship with the state, or parse how the politics of hatred latch on to the soft underbelly of people’s most private vulnerabilities, or properly understand a prisoner’s experience of incarceration, you should talk to them for three hours about their health. Now I work in the archive of the Natural History Society of Northumbria (NHSN), so my entire sense of the past two centuries of the North East’s history is filtered through drawings of birds and flowers, dissection diagrams, daguerrotypes of trees, and minutes of meetings where heavily-whiskered prosperous men displayed the skeletons of extinct creatures to each other. This isn’t at all a bad thing.

The Society has been around for nearly 200 years; it built what’s now the Great North Museum: Hancock in Newcastle upon Tyne, where its offices, library and archive are still tucked away in a small warren of rooms on the top floor. Nowadays its main functions are running a nature reserve, putting on wildlife walks and lectures, and taking care of the archive and library. In its time, though, the NHSN was one of the provincial outposts of the great improvised apparatus of knowledge-producing societies which flowered across the global North in the the first half of the nineteenth century. These societies codified academic and scientific disciplines that now seem unquestionable, developed the modern laboratory and museum, and worked alongside nation states to study, classify and often to colonise the world. Funded by membership subscriptions and private money from the often wealthy individuals who founded and ran them, these were spaces outside of universities and the state but deeply involved with both; dedicated to the free development of knowledge through intellectual exchange, but heavily policed as to who was allowed to participate. In a city like Newcastle, they were places where an emergent industrial bourgeoisie could define itself and manufacture a civic identity within the context of a convivial sociality which was exclusively male and moneyed.

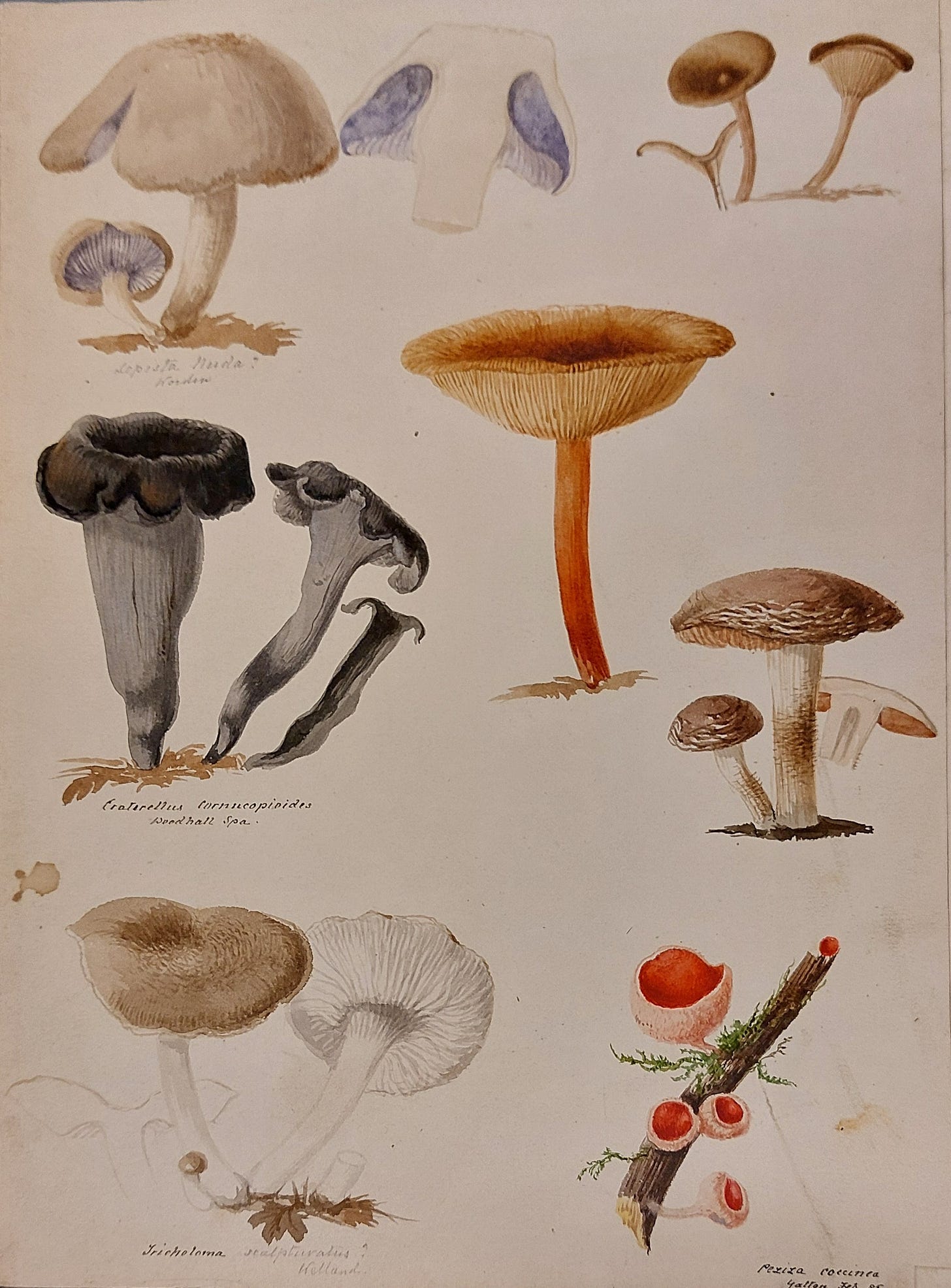

With this in mind, what’s surprising is how heavily weighted the archive is towards art – art, and stuff that while it might not have been conceived of as art is certainly capable of being experienced as it. The natural sciences have always been heavily visual, and in some ways this is more pronounced the further back you go: until the advent of cheaply-reproducible photography, the only way to accurately represent biological specimens was through closely-drawn observational art.